Heavy Cruisers of World War II (Part 2) By Chuck Hawks  Hitler initially told Admiral Raeder that there would be no war with Britain. In 1938 it became obvious that Hitler was moving toward a confrontation with both France and Britain, but he promised Raeder that war would not come until 1946 at the earliest. A balanced fleet (the "Z" plan) was still therefore attainable. If Raeder had known the truth, that the war would start in 1939, he would have focused naval construction on submarines and long range commerce raiders (Deutschlands and long range light cruisers). The ships of interest to us here, the Hipper class heavy cruisers, were part of the "Z" plan. They were all out heavy cruisers designed to be part of a balanced fleet. They were not well suited to the role of commerce raider, lacking both the range and reliability a commerce raider must have to operate independently for extended periods of time. Because of this, when war came prematurely in 1939, they were not well suited to the new role they were forced to play. Never the less, they were impressive ships, the biggest heavy cruisers to fight in W.W.II, and with the single exception of the post war American Des Moines class (17,255t standard displacement), the biggest heavy cruisers of all time. The Hippers were actually built in two batches, the second batch modified as a result of experience with the first, and considerably larger ships than the first. Admiral Hipper, and Blucher constituted the first batch, and Prinz Eugen, Seydlitz, and Lutzow formed the second. Both of the first pair were completed, but only Prinz Eugen was completed from the second batch. We will take a look at the specifications of both groups, starting with Admiral Hipper and Blucher in 1940 (both sets of specifications to follow taken from Conway's and Encyclopedia):

The equivalent set of specifications for Prinz Eugen in 1945 are as follows:

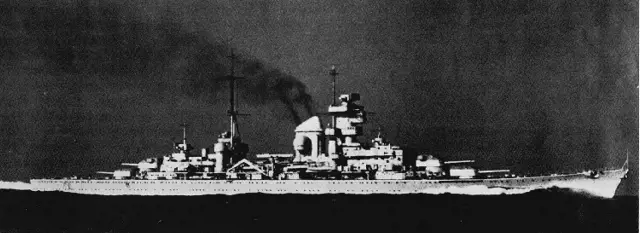

As can be seen from these specifications, these were extremely powerful ships, heavily armed with both guns and torpedoes. All of them had anti torpedo bulges on their hulls. The second batch was improved by a lengthened hull, four anti aircraft directors (instead of two), funnel cap, and clipper bow. Prinz Eugen's designed speed was 32kts, but she made 33.4kts on trials. Although criticized for their comparatively short range, the Hippers seem to have been generally regarded by the German Admiralty as more valuable ships than the similar size Deutschlands. German surface fire control was excellent (only surpassed by the later Allied radar fire control) The AA fire control system was very advanced, tachymetric, with changes in range, bearing, and elevation measured against a stabilized basis. The German 8in AP shells (like the German 11in and 15in AP shells) proved unreliable in service, often failing to detonate after hitting their target. This defect probably saved the British Battleship Prince of Wales (see below). German torpedoes were much like their American counterparts. That is to say, unsatisfactory and unreliable at the beginning of the war, but rapidly improved and successful after the first year or so. Late in the war the Germans developed some very advanced torpedoes. Admiral Hipper was laid down in 1935, launched in 1937, and completed in April 1939. Blucher was laid down in 1935, launched in 1937, and completed in September, 1939. Prinz Eugen was laid down in 1936, launched in 1938, and completed in January 1940. Seydlitz was laid down in 1936, launched in 1939, was about 90% complete in June 1942 when Hitler decreed that she be stripped and re-built as an aircraft carrier. In 1943 Hitler reversed himself and ordered a halt to all aircraft carrier construction. The hull was scuttled in April 1945. Lutzow was laid down in 1937, launched in 1939, and then sold to the Soviet Union early in 1940. She was towed to Leningrad in April of that year, where she served as a floating battery during the siege (she had two turrets installed, only one with guns, when sold). She was in turn shelled by German batteries, hit 53 times, and beached to keep her from sinking in deep water. She was refloated in 1942, and by 1943 was again in use as a floating battery, renamed Tallinn. She survived the war in this condition, and later served as an accommodation hulk until being scrapped sometime after 1956. The three ships that were completed had varied war records. Admiral Hipper made three Atlantic sorties against Allied convoys during the period December 1940 through March 1941, and sank about eight ships in all. Her relatively short range and mechanical unreliability made her a poor raider. During the invasion of Norway, in April 1940, she was engaged and rammed by the British destroyer Glowworm (which blew up), putting a 120ft gash in her side. She was able to continue on to Trondheim, where she silenced the only shore battery that opened fire. In the New Years Eve Battle at the end of 1942, the Hipper (flagship) and the "pocket battleship" Lutzow (the Deutschland renamed) and six destroyers tried to attack an Allied convoy bound for Murmansk from their base in northern Norway. In the very confused twilight action that followed, Hipper sank one British destroyer and badly damaged another destroyer and a minesweeper, but failed to break up the convoy. Hipper in turn came under fire from two 12 gun British light cruisers, who poured a rain of 6in shells at her, hitting her four times. One of those shells set her aircraft hanger on fire, and another punched through Hipper's armor and destroyed No. 3 boiler room, reducing her speed to 28kts, and forcing the Germans to withdraw. Lutzow spent most of the battle stumbling around in a snowstorm, unable to tell friend from foe. Hipper's damage was severe enough to force her return to Germany for repairs. In April 1945 Hipper was dry-docked in Kiel, where she was bombed and seriously damaged by the RAF. Shortly thereafter, on May 2nd, she was scuttled. Blucher was about the least fortunate of the German heavy ships. On her first mission, the invasion of Norway in April 1940, she was the flagship of the task force assigned to occupy the capitol, Oslo. Steaming up Oslo fjord at about 0530AM, she came under fire at only 600yds range by Norwegian shore batteries with 6in and 11in guns, and shortly later was hit by two torpedoes, also fired by shore batteries. Her rudders were jammed in a turn, her engine room flooded, and the ship was on fire. Damage control was unable to fight the fires, and about an hour later a magazine exploded, sealing her fate. She listed further and further over for the next hour, until she lay completely on her side, still burning furiously. Shortly after that she finally sank, at about 0730 in the morning. A few years ago, I was attending the Captains Cocktail Party on the cruise ship Vistafjord. As we passed the Drobak narrows leaving Oslo, I asked her Norwegian Captain where the Blucher went down. "Right about here!" he replied, clearly surprised that any of the passengers on board knew about the incident. The Prinz Eugen was the lucky ship of the German Navy. Her first operation was the famous sortie of the battleship Bismarck. Both Prinz Eugen and Bismarck were brand new ships, having just completed their six month period of "working up". In May 1941 the two heavy ships attempted to break out into the Atlantic via the Denmark Strait. Their mission was to attack Britain's Atlantic supply lines, to sink merchant tonnage. Their orders were to avoid combat with enemy heavy units if possible. Admiral Gunther Lutjens (CinC of the fleet) was determined to carry out these orders to the letter (the two previous fleet commanders had been removed for exercising independent judgment). Lutjens would prove an inflexible and unimaginative leader. Books have been written about the chase of the Bismarck, and the whole story is too long to relate here. Briefly, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were intercepted by the battlecruiser Hood and the battleship Prince of Wales in the Denmark Strait, after having been detected and shadowed by two British heavy cruisers, Norfolk and Suffolk. In the ensuing gun battle, both German heavy ships fired at Hood. Prinz Eugen hit her first, starting a fire amidships which burned out of control. Meanwhile, Hood was firing at Prinz Eugen and Prince of Wales was firing at Bismarck (the similarity of the German ship's silhouettes confused Admiral Holland in the Hood, and Prinz Eugen was the lead ship in the German formation). Hood took only three salvoes to get the Prinz Eugen's range, and the heavy cruiser experienced the uncomfortable sensation of taking fire from a battlecruiser. Fortunately for her crew, she was not hit. Meanwhile, Hood was hit repeatedly by 8in and 15in shells. Five minutes into the battle, as the British ships were turning to unmask their aft batteries, Hood was straddled by a full salvo from Bismarck. A huge tongue of flame shot up from the great battlecruiser, and she broke in half and sank. Only three men were saved from her crew of 1,421. Conventional wisdom has it that one of Bismarck's shells penetrated her deck armor and set off the aft 4in magazine, and in consequence the "X" turret magazine. Another theory is that a shell detonated her upper deck torpedoes. The third version is that the uncontrolled fire set by Prinz Eugen's second salvo cooked off the after magazine or torpedoes or both. My personal feeling is that No.1 above is most likely, since she blew when straddled by Bismarck, and everybody knew that her deck armor was insufficient to protect her against plunging fire from battleship guns. During W.W.I, the British lost three battlecruisers at the Battle of Jutland (including the original battlecruiser Invincible) to magazine explosions. Once again the Admiralty had put a battlecruiser in the line of battle and paid the price. Immediately after the demise of the Hood, both German ships shifted their fire to the Prince of Wales. Within three minutes she had been hit repeatedly by 8in and 15in shells, and was forced to break off the action (by that time she had only two guns still operating). One of Prinz Eugen's 8in shells, fired at a range of about nine miles, had penetrated Prince of Wales armor and tore into a shell handling room without exploding. British records show that Prince of Wales was hit seven times by German 8in and 15in shells, only two of which exploded. Admiral Lutjens forbid pursuing Prince of Wales to finish her off. He was still following his orders (not to engage heavy ships unless forced) to the letter. The German ships resumed course for the Atlantic. The two British heavy cruisers took no part in this fight, by decision of Admiral Holland. Bismarck had been hit three times by 14in shells, which reduced her speed to about 28kts, put her down by the bow, and caused an oil leak which contaminated a significant amount of fuel. That night, Admiral Lutjens turned Bismarck toward the shadowing British cruisers and opened fire on them, forcing them to sheer off. At the same he detached Prinz Eugen for independent commerce raiding. The maneuver worked, and Prinz Eugen got away clean. She eventually made her way to Brest without further incident. The Bismarck sailed on to meet her fate at the hands of the British Home Fleet. Why Lutjens split his force and sent his heavy cruiser away is as obscure to me as why Admiral Holland made no use of the two heavy cruisers at his disposal when he engaged Bismarck. The next major operation for Prinz Eugen was the famous "Channel Dash" in February 1942. The battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau with Prinz Eugen, escorted by six destroyers and fourteen torpedo boats, escaped from Brest (which the RAF had made increasingly untenable for the German ships) back to Germany via the English Channel. This was a strategic withdrawal, but a tactical victory which stung British pride. Both of the battleships set off mines, but all three of the heavy ships made it to German ports. After Hitler's insane order to scrap the major surface ships of the Kriegsmarine in February 1943 (ostensibly to use their guns for coastal defence), the Prinz Eugen operated in the Baltic Sea for most of the remainder of the war. Initially she plus Scheer, Lutzow, Nurnberg, and Emden were saved from the breakers by being classified as "training ships". Ultimately, Hitler must have come to his senses, for while the order was never rescinded, it was not enforced. From August 1944, Prinz Eugen, soon joined by the other surviving ships, provided gunfire support for the army as the fronts slowly collapsed around the Baltic. During this period Prinz Eugen rammed the light cruiser Leipzig amidships, cutting her clear to her keel. For hours, the two ships remained locked together, exposed to enemy air attack which never came. Leipzig never returned to service, becoming a floating battery, but the damage to Prinz Eugen's bow was quickly repaired. At the very end, German Navy and merchant ships evacuated thousands of refugees to the west. Between January and May 1945 about two million Germans were saved from the Russians by seaborn evacuation. Most of the remaining pocket battleships and cruisers survived until almost the end of the war, but eventually Allied air power sank all but Prinz Eugen and a light cruiser. Prinz Eugen was ceded to the U.S. after the war. She was taken to the Pacific (through the Panama Canal), and became one of the target ships at the "Crossroads" atom bomb tests in July 1946. She survived both tests (a lucky ship to the end), intact but radioactive. In December 1946 she was accidentally damaged and was towed to Enubuj reef, where she capsized the next day. So how good were the German heavy cruisers? Taking Prinz Eugen as the example, since she was the last and best of the type, I would have to say she was very good. Her gunnery and fire control were excellent (at least by pre-radar standards). Her torpedo protection was good by cruiser standards. Her armor was a bit light, but proved to be adequate, and her internal subdivision was excellent. Her main battery was typical of the best European cruisers. Her secondary and AA batteries were of a very high standard. Her great size (for a cruiser) contributed to her steadiness as a gun platform, and helped make her hard to sink. Her speed was comparable to others of her breed. Aesthetically, she was a handsome ship, trim, balanced, and deadly looking. She looked similar to, but less massive than, the German capital ships. Her main deficiencies were her range and the general unreliability of the machinery. Actually, only the latter is true. Compared to other heavy cruisers, her range was perfectly adequate, about average. There is no question that the high pressure boilers (1,012psi) and inadequate condensers caused her trouble throughout her life. Except for that one Achilles' heel, Prinz Eugen was a well balanced cruiser. It is impossible to predict how Prinz Eugen would have fared in a shoot out with Zara (who was an ally in any case) or Algerie. On paper they appear about equal. But I confess I like Prinz Eugen's greater size, rugged construction, excellent fire control, and powerful torpedo battery. How would she have compared to the Pacific power's big cruisers? Let's take a look at them next, starting with the Japanese. Japan Other authorities prefer the Takao class. These were improved Nachis, and carried the signature very heavy main battery of 10-8in guns, all in twin turrets (three forward, and two aft). They were the last class designed specifically as heavy cruisers (the later Mogami and Tone classes were officially designed as light cruisers). Their huge bridge structures made them impressive, and recognizable. But there were, after all, two later classes completed. So I am going with the Mogami class. These were the last class before the specialized Tone scout cruisers. Significantly, in 1942 when the Japanese laid down two more heavy cruisers for the Pacific war, it was repeat Mogamis they laid down, not repeat Tones or Takaos. So my conclusion is that it is the Mogami class that the Imperial Navy regarded as their best heavy cruisers. Like most Japanese warships, the Mogami class was designed to be individually superior to their U.S. counterparts. The treaties had fixed Japanese naval tonnage at a lower level than British and American (5-5-3, Britain-U.S.-Japan). Although the Japanese had finally agreed to this, it rankled. One response was to try to achieve qualitative superiority. Of course, all ships are a series of compromises, so to increase the offensive or defensive qualities of a ship without increasing the displacement (which was held to 10,000t by treaty), something must be sacrificed somewhere else. Usually this winds up being habitability, seaworthiness, stability, range, speed, or structural integrity. Of course, another option is to simply ignore the treaty limitations, and build a ship as big as it needs to be to have the qualities you want. This is what Germany did with the Hipper class cruisers. Germany had an excuse, though, as she was never a signatory to the Washington or London naval treaties (nobody asked her to be, she was supposedly limited by the Versailles treaty). In the case of the Mogami class cruisers, Japan chose a sort of "all of the above" solution. They cheated heavily on their stated tonnage, they sacrificed habitability compared to the western powers, and they tried to build the hulls as light as possible (too light as it turned out, the first two ships had major problems with defective welds, hull distortions caused by heavy seas, and even by firing a full broadside), and their stability was marginal. All of these defects were rectified, but at the cost of increased displacement. Ships that were originally stated to displace 8,500t would end up displacing 11,200t, and that was as "light" cruisers, before their 6.1in guns were replaced by 8in guns! Another oddity about the Mogami class is that they really were completed as light (that is 6in gun) cruisers. They carried no less then 15-6.1in guns in five triple turrets. The Japanese triple 6.1in mount had the same diameter turret ring as their 8in twin mount. So when the treaty expired, the four Mogami class visited Kure navy yard during the period 1939-40, and emerged as very heavy cruisers indeed, with 10-8in guns and a newly bulged hull that raised their standard displacement to 12,400t. Complete 1939 revised specifications follow (from Encyclopedia supplemented by Conways):

|