For a good deal on 357 mag ammo go to |

For a good deal on 357 mag ammo go to |

|

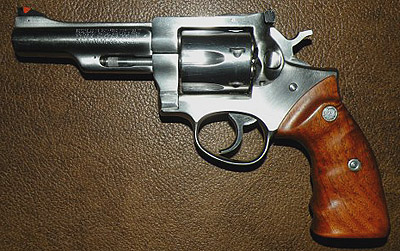

Ruger Security-Six .357 Magnum Revolver By David Tong  Sturm, Ruger & Co. has always been a bit of a dichotomy of a gun company. They use the most modern of manufacturing methods, that of precision investment casting, much as would a jeweler or dental lab, to provide a near-final-sized raw part which thus requires a minimum of machining to become a completed arm. While doing so however, they have embraced neo-classic aesthetics in their arms; examples include the their Blackhawk single-action revolvers, the M77 bolt action and No. 1 fallling block sporting rifles and the Gold Label side-by-side shotguns. In the early 1970s, when the double-action revolver was still the preference of most US law enforcement agencies, Ruger did not have a weapon to compete for this market, nor for civilian home protection users. They rectified this in 1972 with the introduction of the Security Six and Speed Six revolvers, building both of regular blued, carbon steel as well as their proprietary Terhune stainless steel. Security Sixes were generally .357s and had adjustable rear sights, while Speed Sixes were fixed sight guns that were made primarily in .357, but also in .38 S&W Special and 9mm Luger. Both were so-called

“medium-frame” revolvers, in much the same vein as a Smith & Wesson

K-frame, or the Colt D-frame, exemplified by the Diamondback. However, the

Ruger engineers took a good look at the competition’s designs and followed

another path to ensure the new gun’s durability. First, the engineers bulked

up key frame dimensions, including the height of the frame, the thickness of

the top strap and barrel shank support and the cylinder diameter. They also offset

the locking bolt notches on the cylinder to provide added strength to that

most-thin area of each chamber. They comprehensively looked

at the sometimes fragile and hand fitted lockwork of these designs, and in

usual Ruger fashion, over-engineered all the working parts. If one were to do a

comparison detail strip of a Smith, Colt and the Ruger, one would see that pieces

such as the cylinder locking bolt, the hand, the size of the double and

single-action sears on the hammer, one would see that the Ruger pieces are

quite a bit larger. In addition, the Ruger

folks incorporated a transfer bar firing system. While both S&W and Colt used

rebounding hammers to provide a drop safety scheme and S&W had added the

sliding hammer block in 1943 to WWII production “Victory Models” and

subsequently carried this change into civilian production post-war, Ruger felt

that the use of a rising "transfer bar" of steel interposed between

the flat-faced hammer and the frame-mounted firing pin was even safer. Only

when the trigger was fully-depressed in a firing stroke would the transfer bar

rise and allow hammer to strike it and “transfer” that impact to the rear of

the firing pin, discharging the chambered round. Ruger arms are also made of

very good, fully heat treated steels. This means long component life. The frame

itself dispensed with the usual side-plate design and the piece is easily

“field-stripped” for detail cleaning of the lockwork. The downside to this

shooter is that the double-action stroke is problematic. Colt’s hand fitting

and S&W’s selective-assembly methods meant that revolvers were fitted to the

dimensional accuracy of the trigger and hammer pin locations on the frame.

While this added to the cost of production, it means that the finished arm

generally needs no trigger action job to make the stroke smooth from front to

back. The Ruger has notable

glitches in its DA pull. While I admire the way their engineers over-built the

revolver’s internals, and knowing that they were attempting to bulldoze their

way into the marketplace via cost competitiveness by eliminating hand work, in

my opinion the Security Six is a “single-action revolver capable of

double-action firing.” Generally, the single-action pull is nothing to write

home about either, usually at least four pounds with some creep, compared to

the 2-3 pound triggers standard on period Colts or Smiths. However, most shooters were willing to accept this for the strength and price paid. At its introduction, the Colt Trooper was sold for $161, while the Smith M19 went for $143 and the Ruger retailed for $121. Thirty years on and a good used

Security Six can be had in the lower $300 price range. I’ve fitted mine with

the “Reduced” weight spring package from Wolff Springs, yet the DA pull must still

be at least 14 pounds, with the aforementioned glitches. A prior owner had

taken the factory walnut “target” stocks and cut finger-grooves into their

front and reduced their overall girth, making them suitable for smaller hands,

but very slippery with the not-inconsiderable recoil of a full-house .357

round. I will probably have to fit other stocks affording me a more secure grip,

as it squirms beyond my ability to hold it consistently. Ruger chambers are usually

a bit oversized, easing extraction when dirty, if compromising case life

somewhat. They are also usually razor-edged at the rear of the cylinder,

requiring a light chamfer to ease the use of speedloaders. However, and this is the real reason why these guns are a solid buy, they will simply out last any other DA revolver over thousands of Magnum rounds. (With the exception, of course, of Ruger’s follow-on piece, the GP-100.) If one bought a Security Six, one could expect a lifetime of full use and still be able to hand it to one’s children with nary a problem. I once knew of an indoor range that had one as a rental gun and it digested, by their estimate, some 1,400,000 rounds with no parts breakages and minimal maintenance. That is the essence of a good deal! NOTE: This review is mirrored on the Product Reviews page. |

Copyright 2008 by David Tong and/or chuckhawks.com. All rights reserved.

|

|